Lecture 2/7. The medieval world view

Topics this hour:

- Anecdote about Galilei

- The medieval view on man and world view

- Cosmology according to Hildegard of Bingen

- Continuation medieval world view

- Mysticism in the medieval world view

- Mysticism and the Roman-Catholic church

Introduction

Welcome to this second lecture of the course Medieval Dutch Mysticism in the Low Countries.

As I told you last week, in all these lectures I will use the hour before the break to tell something about the cultural-historical context; and the hour after the break to read medieval texts. This hour I will continue with the subject 'the Middle Ages' and thoroughly discuss the medieval realm of thought, the medieval world view. This will thereafter be an anchor when we'll read Hadewijch's visions after the break; and for understanding what medieval people thought about visions and mysticism.

Last week I've tried to sketch a picture of the medieval world. I've discussed the three pillars of the medieval culture (Greek-Roman, jewish-christian and Germanic); the three classes in society (clergy, nobility and farmers/citizens); who could read and write in the medieval society; I've discussed education, schooling, the importance of Latin; and furthermore the rise of the written Dutch literature from the 12th century onward. So last week I've tried to bridge the distance between our time and the medieval society.

Today, before the break, I want to take this a step further. I will explain in more detail the way of thinking of the medieval man. What was his view on man, the world, the cosmos? We will try to crawl into the mind of a medieval person. And there are not only many centuries of space in between us and a medieval person, but their opinions and ideas about the world and the place of mankind in that world also are very different from ours today.

First I will describe the medieval view on man and on the world. What were their thoughts about the universe, the place of the earth in that universe, and the place of man on earth? After that I'll discuss the medieval opinion about mysticism - of the common man and of the church -, that derives from that world view.

Anecdote about Galilei

To get an idea of how different a medieval person thought about the world and his place in that world, I'll start with an anecdote about the Italian physicist and astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564-1642).

During the Middle Ages, and already during the Antiquity, people knew that the earth is round, but they assumed that the earth was in the center of the universe and that the sun and the planets circled around the earth. This astronomical model is called the geocentric or Ptolemaic world view.

The earth in the center

(the Ptolemaic or geocentric world view).

-click to magnify-

Well, in 1632 Galilei claims that the earth circles around the sun: that the sun is in the center and not the earth. Galilei didn't come up with that idea himself, but he defends a theory of the Polish mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543). In his book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) Copernicus worked out a hypothesis that not the earth, but the sun is the immoble center of the universe: the heliocentric world view.

|

Copernicus

|

1543

|

sun in centre (heliocentric)

|

|

Galilei

|

1632

|

sun in centre (heliocentric)

|

So Copernicus' theory dates back to the very last years of the Middle Ages; and at the moment that Galilei publishes his book, in 1632, the Middle Ages officially have ended for almost a century. But the astronomical model that was under discussion here, is rooted very firmly in the Middle Ages.

Because of his statement, Galilei had to appear before the Inquisition (the court of the church). The church demanded that Galilei would declare that he didn't believe in Copernicus' theory and he risked to end up in prison for the rest of his life.

Why was this such an important issue for the Catholic church? It's hard to imagine that the nowadays church would commit astronomers for trial, because they have some theory about black holes or something like that. But that's what in fact is happening in this case. The church believed that the earth is the motionless centre of the universe and that the sun and all the planets circle around the earth. Apparently, the church felt that it was heretical to claim something else.

|

Church

|

|

earth in centre (geocentric)

|

|

Copernicus

|

1543

|

sun in centre (heliocentric)

|

|

Galilei

|

1632

|

sun in centre (heliocentric)

|

Well, there's more at stake here than stubbornness or obstinancy of the catholic church. These are ideas about the earth and the place of man within creation, on which the whole medieval thinking was based. And the medieval view on man and on the world, was fully based on religious convictions.

The medieval view on man and world

I've told you last time, that medieval culture evolved out of three pillars: the Greek-Roman pillar, the jewish-christian pillar and the Germanic pillar, and that Christianity had a leading part in this.

The cosmology (the ideas about the cosmos, the universe, the earth) in the Middle Ages derives from two of those pillars: the Greek-Roman and the christian. Already during the Greek-Roman Antiquity people knew that the earth is round and they were acquainted with five planets.

How did they know during the Antiquity that the earth is round?

The proof of the stars in the sky

As soon as you sail beyond the equator, all the stars in the sky completely change. This is impossible if the earth were flat. The only possible cause is that the surface of the earth is curved.

The proof of the well

When you dig a well on the northern hemisphere, at noon the sun beams will fall into it with an angle. When you dig an identical well around the equator, the sun beams will fall straight into it at that point in time, and they will reach the bottom of the well. This proves that the earth is curved. Based on this, mathematicians were even able to determinate, very accurate, the circumference of the earth.

The proof of the eclipse of the moon

A lunar eclipse means that the shadow of the earth falls on the moon. This shadow always has a round shape, the shape of a disc, never the shape of a flat beam. So the earth is not a flat pancake, but a sphere.

|

|

Ptolemy, a mathematician and astronomer in the Greek Antiquity, made a schematical image of this geocentric world view (that's why it's also called the Ptolemaic model of the cosmos). In the Middle Ages they adopted this view on the cosmos from the Antiquity.

The earth in the center

(the Ptolemaic or geocentric world view).

-click to magnify-

This picture shows the earth as the center of the universe. Thereabout circle successively the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Next to that you see the firmament with the stars and constellations. Still further ahead is the so called Primum Mobile (meaning: the 'first mover') and around that the Empyrean, the residency of God (in Latin: the Coelum Empireum Habitaculum Dei: the 'fiery heaven, God's residence'). So the Empyrean is in fact nothing more but God; the cosmos is God's creation and God embowers that creation and also penetrates that whole creation.

The word 'empyrean' is derived from the Greek empyros, 'fiery', 'consisting of pure fire': in Greek mythology actually the highest heaven was nothing but pure fire. The residence of the christian god still is called the 'fiery heaven', the 'empyrean heaven'.

During the Middle Ages the complete thinking was soaked with religion, from that jewish-christian pillar. Also the ideas about the cosmos and the place of earth and human in that cosmos. Cosmology, the view on the world and the view on man are completely interwoven with religious ideas; it's impossible to cleave the two during the Middle Ages. And because the whole of Europe (between the sixth and the tenth century) became Roman-Catholic, the fundament of this all is the Bible.

And that geocentric cosmos, heaven and earth, was created by God in six days, according to the first book of the Bible, Genesis; and according to the jews this happened approximately 6000 years ago. On the first day, God separated light from darkness, on the second day He created the heaven firmament, and more and more comes into existence: the sea, the plants and trees, and the sun, moon and stars. On the fifth day the living creatures, fish and birds; and on the sixth day the terrestrial animals and human beings. And according to Genesis, God created the human being after His image. So according to medieval faith, the human being is an (unique) divine creation, the only creature formed after the image of God himself.

Regarding humanity, the catholic faith believed in the salvation history of mankind. This history begins, according to Genenis, with creation and will end with the Last Judgement. The christian church presumes that this involves a linear history, with a starting point and an end point (creation and last judgement). This contrary to Antiquity, when people believed in a cyclic history (everything always returns, believe in reincarnation). The Catholic Church rejected reincarnation; they regard life and history as linear, from creation until last judgement.

After creation, man and woman live in paradise. A crucial moment in the salvation history of mankind is the moment of the fall of man. The human being possesses intellect and a free will and voluntarily they then turn away from God; this is the story of Adam and Eve, you will all know it.

The view on man within medieval Christianity is therefore dual: positive and negative. On the one hand the human being is created by God after His image - the human being is image-bearer of God, has a free will, is able to reason, able to love, can choose to do good. On the other hand, since the fall the human being is a sinner - the human is sinful, falls short, is inclined to all evil, is imperfect.

|

|

Salvation history of mankind

- creation (beginning)

- fall of man (turning away from God)

- last judgement (end)

|

But that moment of the fall, that sinful fall, turning away from God, that moment also has been decisive on the cosmic scale: it has determined the place of the earth within the universe. And the earth has gotten the worst spot within the cosmos: it is the motionless center.

Everything in the cosmos is moving, according to the medieval man, out of love for God. The Primum Mobile turns from east to west, and the planets give some counter-motion from west to east (to give an explanation for their different velocities). During this movement, they produce beautiful sounds, and all those sounds together form a beautiful harmony (the so called 'Harmony of the Spheres').

But what about the earth, the static center? The earth is motionless, it doesn't move out of love for God. Furthermore, the earth is at the farest distance from the Empyrean and subsequently from God; the above picture shows that clearly. And in the deepest core of the earth, so the place that is the very farest away from God, there the hell is located.

So the earth is motionless and at the farest distance from God. But furthermore, the earth is situated in the so called sublunary sphere: the region in the geocentric cosmos below the moon. You can see it in above picture: the last celestial body that moves, is the moon. After that you arrive in the sublunary sphere, the sphere of the motionless earth.

Well, this sublunary sphere is very deviating, very different from the other, celestial spheres. First of all, in the sublunary sphere everything is liable to decline, perishableness, and mortality. Paradise was still ruled by eternity, but since the fall, the human being is living in a declining and mortal world. In the celestial spheres, above the moon, everything is eternal.

Second of all, the sublunary sphere is made out of matter, it's a material world, and it consists of four elements: earth, water, air and fire. Adversely, the celestial spheres consist of only one element: ether. These are the etherial spheres (etherial means: thin/airy, immaterial, metaphysical, heavenly).

And on the third place: the earth is inhabited by mankind. The planetary spheres though, are also inhabited according to the medieval man: they are inhabited by angels. These angels are divided in nine choirs or orders; and that is the exact number of the planetary spheres (seven celestial bodies, the firmament and the Primum Mobile). These nine Angels' Choirs are usually subdivided in three groups (the order can vary a bit per historic source). Mostly, the lowest orders (closest to earth) are the Angels, Archangels and Principalities. The middle orders are the Powers, Virtues and Dominions. And the highest three orders are the Thrones, Cherubim and Seraphim. So these highest choirs are closest to God.

|

Empyrean

|

|

|

|

domicile God

|

|

Pr. Mobile

|

|

Seraphim

|

|

|

|

Firmament

|

|

Cherubim

|

|

|

|

Saturn

|

|

Thrones

|

|

|

|

Jupiter

|

|

Dominions

|

|

} dmcl. angels

|

|

Mars

|

|

Virtues

|

|

|

|

Sun

|

|

Powers

|

|

|

|

Venus

|

|

Principalities

|

|

|

|

Mercury

|

|

Archangels

|

|

|

|

Moon

|

|

Angels

|

|

|

|

Earth

|

|

|

|

domicile mankind

|

Since the sinful fall of man, it's no longer possible for God to have direct contact with a human being (which had been the case in paradise). Buth through the angels He still is connected with humanity. The angels are messengers of God, intermediaries between God and mankind.

The lowest choir is closest to mankind, you could imagine this as what are called guardian angels. The second order, the Archangels, only have contact with human beings on very rare occasions, according to the Bible. For example in the New Testament, Archangel Gabriel heralds the birth of Jesus to Mary (others that are mentioned by name are Michael and Rafael).

Origin of angels

Already the Mesopotamian mythology, about a thousand years before the eldest jewish writings, contains winged creatures as messengers or mediators.

The people of the old Mesopotamia distinguished four kinds of gods: earthly gods, water gods, underworld gods and sky gods. Because the sky gods were unreachable, in their mythological body of thought came winged creatures into existence to maintain contact.

During the Babylonian exile the jews copied many images and motives from the Mesopotamian mythology. The god of Abraham, Jahweh, was a one of those sky gods and therefore these mythical, winged messengers also play an important role in the jewish and later the christian writings - then called 'angels'.

The Greek word 'angelos' and the Latin 'angelus' litterally mean 'messenger'. It's a translation of the Hebrew word 'mal'ach' ('messenger').

|

|

So roughly the cosmos in the medieval world view consists of three parts: the earh, created matter, the material sphere (domicile of mankind); the celestial spheres, the planetary spheres and firmament, etherial, created ether (domicile of the choirs of angels); and the Empyrean, the uncreated (domicile of God) - and together they form one whole, one cosmos, one creation.

|

empyrean

|

|

divine (uncreated)

|

|

God

|

|

planetery sph.

|

|

celestial (ether)

|

|

angels

|

|

earth

|

|

sublunar (material)

|

|

mankind

|

Try to imagine what this means. When we look up at night, we see a cold, empty, endless universe. When medieval men looked up at night, in a way they looked to the inside, they were covered by an enormous dome. They were embrassed by God, by spheres they believed were filled with angels and music (although they could not see or hear this, because ether is invisible for the material eye). And they knew that they were in the worst place, the sublunar, where everything is decaying, short-living, mortal; the motionless center, farest away from God.

Dante Alighieri describes a journey

along the planetary spheres/angels' choirs

to the Empyrean (with God as three radiant circles)

in La divina commedia, 1310-1320

(ill. by Gustave Doré, 19th century).

-click to magnify-

Cosmoly according to Hildegard of Bingen

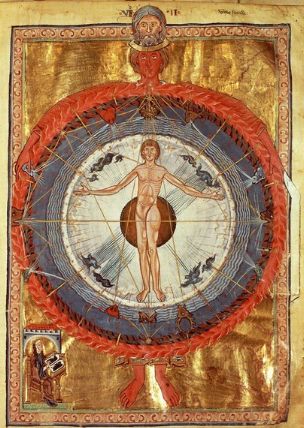

Several miniatures of Hildegard of Bingen (12th century) clearly show this medieval cosmology. In last week's hand-out we've seen the vision 'God and the cosmos' (the second vision in her book Liber Divinorum Operum).

Hildegard of Bingen,

vision God and creation, in LDO.

-click to magnify-

Depicted is a human being in the cosmos: in the middle the spherical earth, around the earth the planetary spheres, domicile of the choirs of angels (the white, waving lines), then the firmament with all the stars (the red dots). Around that the divinity (the Empyrean), depicted as a human figure (with a head, hands and feet), that surrounds and encloses the whole creation. The red colour, as I told before, Hildegard explains as 'God's mother love': God's love encloses everything.

All around animals are depicted, in groups of three at a time, and they are blowing. They represent the powers of God that keep creation in existence. In the left low corner, you see Hildegard herself. She is sitting in her cell and looks up: she watches the vision. On the table is a wax tablet on which she writes down the things she sees and hears. Later a monk drew a miniature of the vision (so she didn't drew them herself).

Hildegard of Bingen,

vision of the creation, in LDO.

-click to magnify-

Another miniature, the vision named 'The creation' (also from the Liber Divinorum Operum), also shows many of these elements. You see again the round, spherical earth in the center of the cosmos, and as the outer circle, the divinity, that encloses creation (the blue divine light and the red divine love). The earth is depicted with all the seasons and in her comment Hildegard philosophises about the idea 'God is life'.

At the left side again you see Hildegard, she watches the vision and writes it down. The strip of parchment, at the bottom, was meant for a text, a short comment, but it's not filled in.

On these two pictures, the planetary spheres and the nine choirs of angels are not clearly highlighted, they're nothing more than white waving lines. But it's depicted in another vision.

Hildegard of Bingen,

vision of the choirs of angels, in the Scivias.

-klik voor vergroting-

Hildegard describes the nine angels' choirs (in her book the Scivias) as above picture. The nine orders of angels are situated around a center. Every choir has it's own characteristics, clearly distinguishable, but within a choir, all agels are alike.

So this is Hildegard's representation of the Angels, Archangels, Principalities, Powers, Virtues, Dominions, Thrones, Cherubim and Seraphim.

All of these 12th-century visions, clearly show the medieval model of the cosmos. The earth is in the center of the cosmos (geocentric world view). Around it are the planets with the angels' choirs, the stars and the Empyrean (domicile of God). And the earth, the motionless center, clearly is the farest away from God.

These pictures visualise how medieval cosmology (the way of thinking about man, the earth and the universe) completely is interwoven with religious thinking. The earth is surrounded by planets and angels, by stars and by God.

The question is asked: how widespread, how generally known was this medieval cosmology? Were these ideas known by the common man? Well, remember I told you last week, that the educational system used by the cathedral schools and monastery schools, was called the artes liberales or seven free arts (the Roman educational system). This consisted of three linguistic subjects and four arithmetical subjects - and these latter four were arithmetic, geometry, music and... astronomy. So everyone who received an education, learned about cosmology.

Well, schooling of course only was accessible for a small group of boys, but later on these men got important positions within society. They became priests, pastors, vicars; every week they preached before the people, held sermons, they took care of ministry (taking care of spiritual welfare), they spoke with their parishioners - and this was all based on that way of thinking and way of believing: the view on the world according to the medieval cosmology and the beliefsystem of the catholic doctrine.

Education always is the transfer of knowledge, the current state of knowledge. So during the Middle Ages, the subject Astronomy will teach the generally accepted state of knowledge from the Greek-Roman and the medieval civilisation. And subsequently the parish churches essentially will reach everyone; for Catholicism was the commonly accepted faith, everyone was catholic and visited church. Of course the priest won't have given lectures in cosmology, but in their sermons and conversations they will have referred to the salvation history of mankind, the nine choirs of angels, the mortality in the sublunary sphere, and so on.

So you may assume that the state of knowledge of that time defined the world view of the priests and from there could seep through to the whole population. So this medieval world view, the cosmology, and this medieval faith system, the catholic doctrine, that were completely interwoven in those centuries, shape the very common background of the medieval way of thinking.

See also the complete hand-out about the Liberal arts and te difference between Artes-literature and scientic texts.

|

|

Artes liberales

Since the Antiquity there were three groups of subjects a pupil could choose to study: the 'liberal arts' (artes liberales: �l�a�n�g�u�a�g�e� �a�n�d� �c�a�l�c�u�l�a�t�i�n�g), the 'mecha�nical arts' (artes mechanicae: like handicrafts or the practice of medicine) and the 'uncertain arts' (artes incertae or magicae, like alchemy or magical recipes).

The word 'artes' ('arts') refered to competence, 'to have knowledge of'. The word 'liberales' ('free') meant that it involved intellectual work, and one had to be free of physical work. The 'seven liberal arts' involved: linguistics, logic and rhetoric� �(�a�r�t�i�c�u�l�a�t�e�n�e�s�s�); and arithmetic, geometry, theory of music and cosmology.

Texts that describe such subjects are called artes-literature. This is sometimes conveniently defined as 'medieval scientific texts' but that is very misleading, since science as we know it today (knowledge based on research, verifiable for others, etc.), didn't yet exist before the seventeenth, eighteenth century.

Artes-literature always is about philosophising and theological theorising from the Bible, theology, the religious tradition or superstition. So this doesn't belong to scientific texts, but to informative, practical or contemplative texts or natural philosophy.

|

|

|

Continuation medieval world view

I would like to return for a moment to the idea of the sublunary sphere and the celestial spheres.

The earth in the center

(the Ptolemaic or geocentric world view).

-click to magnify-

Everything I told you so far about the sphere below the moon and the spheres above the moon, maybe has given the impression that these are strictly separated regions. In the sublunary sphere: immobility, mortality, matter / four material elements (earth, water, air, fire) and human beings. And in the celestial spheres: motion, eternity, one spiritual element (ether) and angels. In the sublunary sphere: no longer contact with God; in the celestial spheres: connection with God.

However, this separation isn't that sharp. The human being even was strongly connected with the celestial spheres.

The fact is that, during the Middle Ages, man was seen as a micro-cosmos, a reflection of the whole cosmos on a small scale. The human is both mortal and eternal as well: body and soul (matter and ether, earthly and heavenly). In fact Hildegard of Bingen's first vision ('God and the cosmos') did show this already: the beams of the stars reach into the sublunary sphere and even touch the human; and the human reaches to heaven: with his/her fingertips he/she touches the beginning of the celestial spheres. In fact the human being is too large for the sphere of the earth. The soul actually belongs to the celestial spheres.

Hildegard of Bingen, LDO vision 2.

-click to magnify-

So the human being consists of a mortal part and an immortal part. The mortal part, the body, is a reflection of the (material) earth, the sublunary; and the etnernal part, the soul, is a reflection of ethereal (immaterial), the celestial spheres.

A concrete example how the human as a micro-cosmos reflects the cosmos, are the elements. The material part of the cosmos, the earthly sphere, consists of four elements: earth, water, air and fire. Likewise the body, the material part of the human, also consists of four elements, namely four bodily fluids (blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm). The element ether, in the celestial spheres, is analogue to the soul. Like ether, the soul is eternal, immortal and immaterial (ethereal).

When a person died, he ascended to heaven (towards the Emyrean, towards God); or he fell into the hell (in the center of the earth). Since the 12th century the idea of a purgatory (a place of fire for purification) was added. In that century people could no longer accept the concept of an everlasting hell and furthermore the Bible stated that it's effective to pray for deceased people. So a statical, changeless heaven and hell couldn't be right. So in the 12th century the pope of that time added the purgatory. But where it was situated in the Ptolemaic model of the cosmos, never became clear to me.

Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias, vision 1-4

The soul leaves the body while passing away and is taken to heaven or hell. The soul is depicted with a bodylike shape.

-click to magnify-

Anyway, according to the medieval way of thinking, the humun being is a micro-cosmos (similar to the four earthly elements and to the spiritual element ether): the human being is material and etherial, mortal and immortal, body and soul.

Well, if we try to oversee the whole medieval world view so far, with an overall view, it becomes understandable why the church reacted so fiercely to the hypothesis of Copernicus and Galilei that the earth wasn't the center of the universe, but the sun probably was the center.

The whole cosmology and the place of man within that creation, based on religious thinking, would no longer be right. In medieval cosmology, everything fits so perfectly, everything is explicable: the earth is the center, the motionless center of the universe, and is situated, since the fall of man, in the sublunary sphere, farest away from God (with the hell in the core), subjected to decline, perishableness and mortality. In the celestial spheres: the planetary spheres with the nine choirs of angels, the Harmony of the Spheres, the everlasting and immortal, and the all embowering Empyrean, God's residency.

If the sun should turn out to be the center of the universe, this whole image of the cosmos, earth and man, created by God, would collapse as a house of cards. Suddenly the earth would be situated in between the planetary spheres, no longer at that worst spot of standstill and mortality, but moving in between two orders of angels, no longer with the deep hell farest away from God.

So in that way it's understandable that Galilei's claims were judged as heretical - there was more at stake than just an astronomical issue, this was also about the christian world view and the relation between man and God since the fall.

Sure enough, Galilei did declare before the Inquisition that he didn't believe Copernicus' hypothesis, so he didn't go to prison. But he was sentenced to life long house arrest. Legend says that, after this judgement, Galilei supposedly would have mumbled: 'Eppur si muove' - 'She moves anyway!' But it will be impossible to ever determine if this truly has happened.

Mysticism in the medieval world view

Well, I hope that you now have a general image of the way of thinking of the medieval man, which is very different from our current view on man and on the world. That's especially because the medieval view on the cosmos, the earth and mankind, is based on religious concepts, christian concepts.

The moment of the fall of man is crucial for the medieval view on man and world. From that moment on, the human being, in the sublunar, the material sphere, no longer was in direct contact with God.

Within the framework of this course, centainly in all of you is now cropping up an urgent, burning question. And that is: if the church says that it's heretical to claim that the sun is the center of the cosmos - wouldn't the church likewise say that it's heretical when a mystic claims nevertheless to have contact with God? In fact that became impossible after the fall of man. Even when the birth of Jesus was announced, it was Archangel Gabriel, according to the biblical story, that visited Mary; God didn't tell her that Himself in a mystical experience.

Aren't mystical experiences, described by medieval mystics, very presumptuous and, from the church's point of view, even heretical?

The answer is: no. Although many mystical authors have been brought before the Inquisition (the church's court), the mystical experience in itself wasn't heretic. To understand this, we'll have to pay attention to the second crucial moment in the salvation history of mankind.

The first crucial moment was, according to catholic faith, the fall of man: the human being turning away from God. The second crucial moment in the salvation history of mankind, is the arrival of Christ on earth, his crucifixion and resurrection. Jesus, as the medieval man believed, took the sins of men upon Him, and thus He reconciled man with God. He restored the contact between God and man, and established a new covenant, a new Testament. Christ is in that way of thinking 'the road, the truth and life', because 'no one will reach the Father but through me' (Joh. 14:6): so Christ is in the medieval world view the road towards God, the road that's leading back to God.

|

|

Salvation history of mankind

- creation (beginning)

- fall of man (turning away from God)

- Christ's coming (God tending towards mankind)

- last judgement (end)

|

This narrative of the salvation history of mankind is used by christians to try to understand or explain the history of the earth and the place of mankind in it (from the creation of earth and man; to the fall of man; then the coming of Christ who shows the way back to God; and finally the Last Judgement in the future).

This narrative of course is based on the stories in the Old Testament about the fall (Genesis, 5th or 6th century B.C.) and in the New Testament about Christ (beginning of our calendar era). When you place these stories in the context of the history of literature, of that time and preceding (a large complex of stories about gods or heroes from the Greek and even still older Mesopotamian mythology), then the many parallels are remarkable. The influence of Mesopotamian mythology can in fact be traced back to the Babylonian exile of the jews, during the most part of the sixth century B.C.: during that time they borrowed many images, motives and narratives of the (much older) Mesopotamian mythological stories.

Some examples of already well-known and often used themes and motives:

• the classical narrative of the rescue (the strayed off sheep, that the shepherd is searching for);

• the explanation of the origins of something, like in the many myths of origin (for example things like: why is man wicked, why is the earth a place of decline and misery - in this case because of the fall of Adam and Eve);

• the image of a holy garden with a tree in which a snake is living (in the Sumerian myth of Inanna);

• the hero who is the descendant of a god and a mortal (in mythology called demigods or half-gods; like Achilles, Aeneas and Perseus; and later according to several stories in the christian gospel also Jesus);

• the story of the virgin birth, that had to underline the extraordinary exceptionality of the god, hero or saint (for example Perseus, Attis, Buddha, Krishna, Horus, Mercury, Romulus, and others - decades after Jesus' death this story also arose about his impregnation);

• the great theme of a sacrifice or self-sacrifice (remember the many classical gods and heroes' stories in mythology, since Mesopotamia, about self-sacrifice and about the god that dies and later returns from the underworld, like Dumuzid, Osiris, Attis en Dionysus);

• and giving hope (in case of Christianity: you can be saved, since Christ's life on earth, if only you convert to Christianity).

The jewish and christian stories clearly form part of this complex of religious stories from the ancient times. This history of ideas, that we can read back to the earliest clay tablets of Mesopotamia, goes on continuously, changes again and again, and expands all the time with new stories, always a little bit changing the to fit the cultural and societal developments, and also the texts of Hadewijch and Ruusbroec are part of this. The two key moments in the christian story are then coherently related: the fall is the human being turning away from God; Christ's coming to earth is God tending towards mankind.

So Jesus is very important in christian-theistic mysticism and we will encounter him later when reading Hadewijch and Ruusbroec. Many mystics regard Christ to be God Himself, coming to the earth to restore the connection and to show mankind the way. Christ is: God as human being. And thanks to this partly human nature, He is closer to the human being and it's easier for a human to connect with.

By the way, it was only during the fifth century, after over 75 year of increasing fray and quarrel, that it was decided that Jesus was both human and divine - it was not because of the gospels, but it was an uncompromising demand of non-jews from especially the Hellenistic culture (the dyophysitism doctrine, 5th century).

Hildegard of Bingen, LDO, vision 1

God in the shape of a human, a personal God, depicted as male and female. Holding Christ, the Lamb of God.

-click to magnify-

At the beginning of the hour I asked the question: what was the medieval opinion about mysticism based on the medieval world view and view on man? If all has gone well, the answer should be clear for every one of you.

Really try to form an overall view of all the previous information in your head: the medieval man really believed in that sublunary sphere, the choirs of angels around it, God surrounding the whole creation, angels acting like messengers of God. And he believed that a human being was a micro-cosmos, that his soul belonged to the celestial spheres. And he assumed the salvation history of mankind: Christ had established a new covenant between God and mankind, had restored the connection.

In that way you can imagine, that one could believe that visions and mystical experiences could come from angels and thus from God Himself, and that they could be interpreted as miraculous, exalted, sacred or holy. Imagine: a message from God Himself, from the Empyrean - for contemporaries that must have been impressive, overwhelming, sensational.

In short: visions and mysticism seamlessly fit in the world view and view on man of that time, and because of this a medieval man could interpret them as true and holy.

Were visionaries and mystics consequently also worshiped as a kind of enlightened masters, oracles or saints? No, certainly not (at best by a small group of followers, sympathisers who were convinced of the sincerity of that specific mystic). Seers and mystics also could be juged as false (fake, not real), or hellish (inspired by a devil), or heretical. Their words were limited by the established and mighty church, that was founded on the Bible, Christ, the prophets and their own doctrine and dogma's. And as I told you last week: everyone who deviated from the orthodox doctrine was identified as heretical.

There has been a lot of friction between the Catholic Church and mystics. I will end this hour with that: the relationship between the mystics and the medieval church: their connection and friction.

Mysticism and the Catholic Church

First the mutual connection between church and mystics.

Due to the second crucial moment in the salvation history of mankind, the coming of Christ, the mystical experience is acceptable for the Catholic Church. But even the idea of meeting God and even uniting with God is already present within the church. One example is in the Bible, the famous statement of Jesus: 'I and the Father are one'. Another example is among the Sacraments, the Eucharist during the Mass (consumation of the Host). This is clarified more explicitly in the hand-out.

The idea of meeting God within the church

Within the church the idea of meeting God and even uniting with God is already present. Two examples: one from the Bible and one from the Sacraments.

(1) A Bible verse that is often mentioned in relation to this subject, is Jesus statement: 'I and the Father are one' (John 10:30); and 'I am in my Father and you are in Me and I am in you' (John 14:20). Hadewijch even refers to the latter in one of her letters. Another example is one of the Beatitudes, the blessings by Jesus, in the Gospel of Matthew: 'Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God' (Matt. 5:8).

(2) Also within the christian church you can find a form of human uniting with God - especially during the Eucharist, one of the most important sacraments of the Catholic church (a 'Sacrament' is: a sacred rite within the church).

During the catholic Mass, the Eucharist is celebrated: the remembrance of the Last Supper. The priest repeats the words that Christ spoke during his last supper. He blesses the bread, breaks it and hands it around with the words: "Eat this, this is my body". After that he blesses the wine and hands it around with the words: "Drink this, this is my blood, the blood that is shed for the forgiveness of sins". According to the catholics, a wonder happens at the moment the priest blesses the bread and wine: this really changes into Christ's body and blood.

So the believers literally take in Christ, incorporate Christ in themselves. And in fact this is a form of a mystical experience, yes, very literally, in a material way, but even so a unification with Christ. Every catholic will do this during Mass every Sunday, in monasteries this even happens every day. But this shows, that the mystical experience is very close to the experience of the 'ordinary' believer and to the sacraments and doctrine of the church.

So the mystical experience was, since the coming of Christ, an acceptable phenomenon for the Catholic Church - both within the christian world view, the salvation history of mankind, the sacraments, the Bible and the doctrines, the belief system.

|

|

As you see, mysticism is acceptable for, and even present in the church. Beside this church's connection to mysticism, there is also the mystic's connection to the church. Mystics are firmly rooted in the church and in the Bible and in the christian imagery.

Besides the idea that unification of a man and a god is possible, there are also other elements of Western mysticism that have their foundations in the Bible, like describing God in terms of love and a large number of biblical images (eagles, a new city, etc.). You can find examples in the same hand-out.

Mystical texts are rooted in the Bible

Within christian mysticism, God often is described in terms of love. An important foundation for this is found in John's first letter, in which he writes: 'Anyone who does not love, doesn't know God, because God is love. (...) God is love. And whoever remains in the love, remains in God, and God in him (1 John 4:8+16).

Love not only is an essential point in christian mysticism, as we will see later on, but already is the foundation of the New Testament, in Jesus' own words. In the gospel according to Matthew, Jesus is asked what is the most important commandment. He answers: 'Love the Lord, your God, with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your intellect. This is the first and greatest commandment. The second is like it: love your neighbour as yourself. All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments' (Matt. 22:37-40).

Furthermore medieval visions often refer to biblical images and verses, especially the Song of Songs (love lyric, Bernard of Clairvaux, love) and the Revelation of John (visionary images, angels proclaiming messages, the image of the eagle, the new Jerusalem, and so on).

Mysticism isn't necessary for christian faith, but christian faith and convictions are necessary ingredients for christian mysticism.

Mystical texts are always firmly rooted into the society, the church, the faith and way of thinking and the spirituality in which they come into existence, they evolve out of this.

|

|

Alright, this was all about the connection between church and mystics. Henceforth about they way these forces were colliding, the tension between the two. Within christianity, there were several frictions between the established faith, the church, and on the other hand the spirituality, the mystics.

On the one hand, you have the christian church, which is based on revelation: God is revealed by prophets and by Jesus, the Christ. In the course of the centuries, people formulated a doctrine based on that, with indisputable truths, dogma's, and with rituals and sacraments. The church also was familiar with a more inward mentality: first the prayer, the inward orientation of man towards God; and secondly the concept of grace, the orientation of God towards man. Only having faith wasn't enough, it was also necessary to to pray, to take part in the sacraments, to receive God's grace and to do good works.

But an inward path, spiritual experiences, are not a requirement to be a good christian. The mystical experience was accepted, but could also sometimes feel as threatening: the church hardly had grip on it and felt needless in it's mediating role between man and God. And even more problematic: they couldn't verify these experiences. Every self-proclaimed clairvoyant could, concerning all sorts of different and strange ideas, refer to visions and claim that he now holds the final truth - and every mystic (could be hundreds of them) could assert something else, contradict each other, etc. So there the church strongly drew the line: as soon as mystics made statements that were not conform the church's revealed truth and doctrines, then these mystics could be accused of heresy and even end up at the stake.

On the other hand, you have the mystics and they have another approach towards faith, an inward, personal, spiritual approach. Revelation is not the core for them, but deepley living through their faith, with an emphasis on love for God and God's love for the human being. Mystics place the feeling, the experience, opposite the revelation (and at least it's clear, in all the texts we read during this course, that they themselves were really convinced that it was in fact an 'experience', that suddenly happened to them and that they indeed im-mediately did experience a littlebit of the divinity). Although they place their 'experience' opposite the 'revelation', that doesn't mean they reject the revelation and christian faith; on the contrary (you could say: they fully want to live through it).

By the way: in literature this is often depicted as being completely oppositive, but in a way the church and the mystic do in fact exactly the same thing: they invoke to an invisible and unverifiable authority to claim that they possess a certain absolute truth, that can't be to criticised or doubted. Since the Enlightenment and science we of course know that this isn't a valid argumentation (although you still can find this within religions and spiritual and esoterical groups). Anyway, back to medieval thinking.

Neither do mystics reject the institute of the church, although they can criticise it, like Ruusbroec, as we'll see later on. But the medieval mystics remain a part of the church, they attach importance to for example the Eucharist. They don't want to turn to another path, without the church, but they want to approach faith in a spiritual manner, within the christian church, within that christian community, within the christian faith.

So it's clear: on both sides you see friction and acceptation. But from the medieval point of view, from the medieval view on man and cosmos, the mystical experience, meeting God, is possible since Christ's coming to earth and thereby acceptable, credible for the medieval man. And more than that: visions and mystical experiences could be interpreted as miraculous, sacred, holy, coming from angels or from God Himself.

Huge difference between the nowadays way of thinking and that of Hadewijch / Ruusbroec

The medieval cosmoloy, the Roman-Catholic faith and the jewish-christian Bible (the medieval way of thinking and of believing, which are completely interwoven) are important foundations for the content of Hadewijch and Ruusbroec's oeuvres. It's the stage on which Hadewijch's visions take place; it's the framework in which Ruusbroec developes his mystical thoughts, his range of ideas.

The difference in the view on man and on the world between a medieval man and a present-day man, is immense. It's important to realise that, to be able to understand Hadewijch and Ruusbroec's text from their head, from their way of thinking.

These days we know from scientific research that the universe is approximately 14 billion years old, contains billions of star systems, is expanding endlessly and that the Earth floats somewhere in a spiral arm of the Milky Way. We can understand man as a primate, evolved ('only' about 300,000 years ago) out of a long history of evolution, and who started to imagine gods after the image of a human being. In any case, for the modern man (studying) cosmology, astronomy, are detached from faith.

The medieval man however, assumed that the universe was much smaller and easier to oversee. It would exist about 6000 years, would consist only of our solar system and a circle of stars around it, would be completely filled with angels and enclosed by God. The whole universe in this way of thinking centred around the Earth, the human being was the centre point, literally and metaphorically. Human beings furthermore were beings created by God, divine creatures, created after God's image. The importance of man, centre and highlight of creation, can't be overestimated.

If you really want to understand what Hadewijch and Ruusbroec meant with their texts, you'll have to keep in mind the underlying, medieval way of thinking. If you read their texts from current concepts or spiritual convictions, then you'll end up in your own head. But if you read the texts from the above discussed view on man and world view, then it becomes possible to cast a glance inside their head.

Recapitulation

This last hour was about the medieval way of thinking: the world view and the view on man and the ideas about mysticism based on that way of thinking.

• The medieval way of thinking is based on the assumption of the Ptolemaic or geocentric world view: in this cosmological model the earth is in the centre of the universe.

• The cosmos can roughly be divided into three parts:

- the earth, the sublunary sphere (residence of mankind)

- the planetary spheres and the firmament, the celestial spheres (residence of angels)

- the Emperean (residence of God).

• This cosmology is related to the salvation history of mankind. The four crucial moments in this salvation history are:

- creation (the beginning)

- the fall of Adam and Eve (man turns away from God)

- Christ's coming to the earth (God tending towards humans)

- the Last Judgement (the final end).

• Because the cosmology and the salvation history of mankind are interconnected, it's heretical to diverge from the geocentrical cosmology.

• The sinful fall of man (man turning away from God) determined the place of the earth in the universe: in the sublunary sphere, the farest away from God. There's no longer direct contact between man and God.

• The sublunary, under the moon, is declining and mortal, consists of four elements (earth, water, air, fire) and is the domicile of mankind. The celestial spheres, above the moon, are eternal, consist of one element (ether) and are the domicile of the nine choirs of angels.

• A human being is a microcosmos: a reflection of the cosmos. Since a human being is material and etherial, mortal and immortal, body and soul.

• Mystical experiences are not heretical: since Christ's coming to the earth (God tending towards man) the contact between man and God was restored. The experience is not only acceptable, but could even be seen as holy, coming from angels or from God Himself.

• The medieval way of thinking and the medieval faith are completely interwoven. Together they form the foundation under the mystical ideas of Hadewijch and Ruusbroec.

- the medieval cosmology

- the Roman-Catholic faith

- the jewish-christian Bible

After the break

After the break we will look into two distinguishable religious experiences of Hadewijch (visions and mystical experiences) and we will see how they are related to each other and how they can be understood from the medieval world view.

Background information

The course Medieval Mysticism in the Low Countries consists of seven lectures. The mystical writings of Hadewijch and Ruusbroec will be read and understood from their cultural-historical context.

• About this course Medieval Mysticism in the Low Countries: content and layout.

• Background literature about the Middle Ages, Hadewijch, Ruusbroec and medieval mysticism.

• About the teacher Rozemarijn van Leeuwen.

• Read the reactions or leave a comment.

• Texts of Hadewijch and Ruusbroec: fragments in Middle Dutch and nowadays Dutch.

Original Dutch course

• Lecture 2/7 in Dutch: Het middeleeuwse wereldbeeld.

Copyright

© Above lecture is part of the course Medieval Dutch Mysticism in the Low Countries, by Rozemarijn van Leeuwen (1999-2001).

It's not permitted to copy this text digital or in print and/or to publish it.

∗ ∗ ∗

Follow the whole course Medieval Dutch Mysticism in the Low Countries online:

|